HLI is proud to celebrate the success of Dr. Janice Leung and Dr. Scott Tebbutt, who along with their co-applicants and research teams, have received over $1.8 million in funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Fall 2025 Project Grant competition. This funding will support important new research aimed at improving care for people living with lung disease, heart transplants, and health inequities across Canada.

Understanding COPD Beyond Smoking

Dr. Janice Leung will lead the MAPLE-SEED Study, a project focused on understanding why some people develop chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) even though they have never smoked. COPD is a long-term lung disease that affects breathing and impacts more than 2.6 million Canadians.

While smoking is a major cause of COPD, it does not explain all cases. About one in five people with COPD have never smoked, suggesting other factors play an important role. Dr. Leung’s research looks at how life experiences and living conditions such as childhood hardship, income level, education, air pollution, diet, and neighbourhood environment can affect lung health over time.

The study focuses on changes in the body that occur at the molecular level, specifically through a process called DNA methylation. In simple terms, DNA methylation acts like a biological record of the experiences a person has had throughout their life. These changes can also reflect how quickly the body is aging, sometimes referred to as a “biological clock.”

Dr. Leung’s team hypothesizes that long-term exposure to social and environmental challenges speeds up biological aging and increases the risk of COPD and poor breathing outcomes.

Using information from two large Canadian studies that follow people over many years, the research will:

- Explore how life circumstances and resulting changes in DNA methylation affect lung health

- Identify risk factors for biological aging and COPD – and potentially ways to improve prevention and treatment

In the long term, the applicants hope that this work leads to the development of a simple blood test to help identify people at higher risk of worsening lung disease.

This research brings together experts from many fields, including lung medicine, public health, biology, and data science. The goal is to help prevent COPD, improve early detection, and reduce health disparities.

Improving Early Detection of Complications After Heart Transplantation

Dr. Scott Tebbutt’s research project focuses on improving care for people who have received a heart transplant. Over time, many transplant recipients develop a condition called cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV), which causes the blood vessels of the transplanted heart to narrow. CAV is the leading cause of late transplant failure.

Currently, CAV is usually detected through invasive heart tests, often only after symptoms appear. Dr. Tebbutt’s team aims to develop a simple blood test that can detect signs of CAV much earlier, before serious damage occurs.

The research will look for small changes in the blood such as proteins and molecules that signal early injury or inflammation in the heart. By studying blood samples collected at different times after transplantation, the team hopes to identify patterns that clearly separate healthy recovery from early disease.

This research project will:

- Identify early warning signs of CAV using blood samples

- Track how these signals change over time in transplant patients

- Test how accurately these blood markers can predict disease

- Combine multiple blood signals into a reliable early-detection tool

Led by Dr. Tebbutt and Co-Applicant and HLI Research Associate Dr. Chengliang Yang, the long-term goal of this research is to improve monitoring, reduce invasive testing, and help patients receive treatment sooner.

Making Research Matter for Patients

Together, these CIHR-funded projects reflect HLI’s commitment to research that puts patients first. By studying how social conditions affect lung disease and by developing earlier, less invasive tests for heart transplant complications, these projects aim to improve quality of life, reduce health disparities, and support better outcomes for patients across Canada.

Congratulations to Dr. Leung, Dr. Tebbutt, and their research teams and co-applicants on being awarded these project grants.

On January 19, 2026, Zeren Sun, a PhD candidate working with Dr. Pascal Bernatchez, gave a talk as part of the ongoing Seminar Series at the Centre for Heart Lung Innovation (HLI). The presentation, titled “The Interplay Between Circulating Lipoproteins and Intramuscular Lipids in the Pathogenesis of Dysferlin-related Muscular Dystrophy,” explored the role cholesterol plays in muscular dystrophy (MD), a condition that causes progressive muscle weakness.

Zeren’s research focused on how imbalances in cholesterol levels, both in the blood and within muscle cells, could contribute to the worsening of MD. Healthy muscles depend on a proper cholesterol balance, something patients on cholesterol-lowering medications called statins know all too well, as they often cause statin-associated myopathies, such as muscle pain. But in people with MD, this balance is also disrupted, but differently. Zeren shared how disruptions in cholesterol can interfere with how muscles process fats, leading to muscle damage and reducing the ability of muscles to repair themselves, especially in the absence of a protein called dysferlin.

Using patient data, mouse models, and lab-grown muscle cells, the Bernatchez lab found that it is the presence of harmful “bad” cholesterol particles, the severity of MD is worsened. Their research also suggests that dysferlin might help control how cholesterol moves within muscle cells, which could lead to potential new treatment options. Additionally, certain dietary fats may help improve cholesterol balance in the muscles, offering a possible approach to managing MD. Zeren’s work emphasizes the importance of understanding how cholesterol affects muscle health and suggests that targeting cholesterol pathways might help improve treatment strategies for MD.

If you want to connect with Zeren and learn more about his work, feel free to visit his ResearchGate profile here: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Zeren-Sun

Yejin Kang Explores the Link Between Cholesterol and Muscular Dystrophy

On January 12th, HLI hosted another insightful session in our ongoing Seminar Series. This week, Yejin Kang, a Postdoctoral Fellow at Bernatchez Lab, shared her exciting research on how cholesterol affects muscle health, particularly in the context of muscular dystrophy.

Muscular dystrophy (MD) is a group of genetic conditions that cause muscle weakness and damage. Yejin’s talk, titled The Role of Circulating Cholesterol in Muscular Dystrophy and Muscle Regeneration, explored how changes in cholesterol levels can worsen the effects of this disease and even hinder the body’s ability to repair muscles.

One key takeaway from Yejin’s work is how statin intolerance, a condition that leads to muscle pain, can demonstrate how sensitive muscles are to fluctuations in cholesterol levels. Bernatchez’s lab has been studying the relationship between cholesterol and muscle dysfunction, using pre-clinical models and human samples to uncover new insights. In one experiment, they found that an unhealthy cholesterol level dramatically worsened the condition of mice with muscular dystrophy, leading to severe muscle wasting.

Yejin’s research doesn’t stop at understanding the problem. She is also working on finding better ways to prevent or treat this muscle degeneration by studying how different cholesterol levels impact muscle healing. The team is specifically looking at a group of mice with a genetic mutation similar to one seen in humans with muscular dystrophy, using them to test how cholesterol diets affect muscle regeneration after injury.

Her work is part of a larger effort to understand how metabolic factors like cholesterol can play a role in muscle diseases and could eventually lead to new treatment options.

The seminar was a wonderful opportunity to learn about the real-world impact of cholesterol on muscle health, and Yejin’s contributions to this important area of research are invaluable in the quest for better treatments for muscular dystrophy.

If you want to connect with Yejin and learn more about her work, feel free to visit her ResearchGate profile: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Yejin-Kang

Dr. Stephen Wright joined the HLI as a new Principal Investigator (PI) in May, 2025. He completed his training in exercise and circulatory physiology, and now researches the mechanisms of how the lungs and heart adapt to functional changes across the health spectrum and life span. More specifically, he focuses on how one’s heart and lung work together, and how exercise capacity changes throughout life under different health conditions.

Research Focus and Scientific Vision

What is the focus of your research?

I focus on how the heart functions, how it works with the lungs, and how changes in the function or health of one organ affect the other. This involves studies of how heart and lung function change during exercise, and how interactions between these systems, at an organ level, influence how much blood the heart can pump and how much exercise or activity people can perform. My research also focuses on how heart function changes across the lifespan in healthy or unhealthy aging(for example, during the development of heart disease). I’m also interested in how heart function in health and disease impacts lung function.

What are the big questions that you want to answer?

At the acute/organ level, I want to understand how the whole heart works. Historically there has been a lot of focus on left ventricular function. That makes sense because the left ventricle is the most accessible heart chamber to study, and is the most directly related to cardiac output and oxygen delivery, so problems in the left ventricle are very impactful. However, the heart consists of interlinked muscular bands that form 4 inter-dependent chambers, and each of them can have an important influence on overall heart function. Usually, the heart can generate enough cardiac output that even when people have problems in their right ventricle or left atrium, they do okay at rest. However, impacts may be felt during exercise. And if problems in those chambers occur in addition to left ventricular dysfunction, the impact can be severe.

Looking at the bigger picture, when someone has a heart or lung problem, I want to understand the cascade of events that ultimately leads to their cardiac output being inadequate and the person feeling limited in their daily activities. If a gear in a watch gets damaged, it has an impact on all the other gears it interfaces with, which ultimately impairs the overall function of the watch. I’d like to understand how big problems like heart failure or COPD limit people’s ability to exercise, and what parts of the system we can put back into place to help people function and feel better.

What sets your research apart from others in our centre? And conversely, in what way do you think your work is/will be complementary to what is being done in the centre?

We have groups in our centre looking at many different aspects of the intersection of heart, lungs, and exercise – for example, exercise and immune function, or pulmonary physiology and breathlessness, and how physical training affects diseases. I think I bring a deeper cardiac function perspective. Ultimately, the heart is a muscular pump, and I focus on how the heart fills, how it ejects, and what influences those two functions. My interests in and understanding of exercise and pulmonary physiology allow me to meet people where they are and find mutual interests and solve problems in overlapping areas.

Training Background and Pathway to an Academic Career

Can you tell us about your training?

Most of my studies were at the University of Toronto. I did my undergraduate degree in Kinesiology, and then my master’s in exercise science. At that point, I was studying heart function with ultrasound in endurance-trained athletes. I became really interested in heart function, more so than exercise performance, so I jumped tracks from exercise science to medical science.

I did my PhD studying heart function invasively, working in a cardiac catheterization lab, which was a really fun experience. After having spent seven years on campus in the athletic centre, moving over to a hospital was very different. I got exposure to the clinical world. During my postdoctorate, I finally broke the UofT orbit and came out west to UBC’s Okanagan campus. I worked with Professor Neil Eves there, which was an opportunity to learn about pulmonary physiology. I spent six years at UBCO, looking mainly at how breathing impacts heart function, how that interaction changes as people age, and whether it changes the same way in males and females.

Was there a turning point in your career?

I wouldn’t say turning point, but there were definitely impactful points. For example, I’d been interested in cardiovascular physiology since the third or fourth year of my undergraduate, but towards the end of my master’s degree, I really became fascinated by the heart. I felt like I wanted to put everything else on hold to learn more about clinical cardiovascular physiology.

Another important moment was during COVID, because it would have been an easy time for an off-ramp. Everything was hard, especially doing human research. However, it became clear that I cared about what I was doing enough to bash my head against the wall for two years to make things work, to find ways to stay productive, and to answer the questions that I could.

So I suppose, there weren’t really turning points in my education, but reiterations that I was enjoying what I was doing.

“Of course, there are hard days in everything, but for the last 15 years, I have woken up pretty much every day excited to do what I do.”

Was becoming a PI something you wanted from the start?

No, it was not. None of this was my original plan. I originally planned to study engineering. But I got into health sciences instead. So, I did a year in health sciences and then transferred into kinesiology. I then planned to be done with university in 5 years to become a gym teacher, which, of course, didn’t happen. By the middle of my kinesiology degree, I was interested in physical therapy and spent two placements in clinics. And then, right at the end of my undergrad, I realized that although I found physical therapy interesting, the experiences I had had weren’t something I could see myself doing on a daily basis.

I then decided to try doing research as an undergrad for a year and completed my honours thesis. I liked it enough to do my master’s degree, after which I was still enjoying research, so I did my PhD. Towards the end of my PhD, I started to realize that this could be my long-term plan. Since then, over the past seven years, I’ve set myself up more and more to prepare for an independent investigator position.

That being said, looking back, all the things that I was interested in at some point are actually still part of what I do. For example, I look at heart function and hemodynamics through an engineering and physics lens. My departmental affiliation is with physiotherapy. And my long-term goal is to understand what is going wrong in people’s systems so that we can develop treatments and exercise training approaches that help individuals feel better. All of my previous experiences shaped where I ended up in the end, but not necessarily by design.

Words of Advice for Trainees

If you were to talk to someone about to enter grad school or start a postdoctoral position, what advice would you give them?

“I give this advice to all trainees: before starting something, whether it’s your master’s program, or especially a PhD program, do your homework.”

Understand what you’re getting yourself into and make sure that it’s something that is a good fit for you and something that excites you. I find that some trainees will take an opportunity just because it’s there, or it’s good, but not necessarily because it’s the right opportunity for them. However, it is really important to do your homework and learn about your supervisor and the lab that you are trying to work with.

I’ve been very fortunate to have had extremely good experiences in my journey. But those aren’t entirely by chance – I researched every opportunity that I had ahead of time to make sure – as sure as possible – that it would be a good experience.

What should trainees look for in such opportunities?

To me, the best opportunity is an overlap between work that is intrinsically interesting to you, and important to others, in a positive environment. Especially for PhD students, I hope your work is interesting enough that you will get out of bed and go do it, even on the hard days. That being said, it should also be important to society, so that your supervisor will invest time and effort into the work, and so that journals will publish it. And then the third important point is finding a research centre, group or lab that can do the work and that cares about where you want to go and how they can help you reach your goals, whatever they might be.

Would you elaborate on the importance of finding a good supervisor?

There is a lot of overlap between supervisors who are successful and supervisors who want to help you succeed, but not always. Do your homework – great supervisors are proud of their trainees and will be happy for you to talk to their current or former students before you sign on. They care not just about how you can benefit their project, but understand where you want to go and how they can help you get there.

I was my PhD supervisor’s first grad student, but I talked to her residents and her staff, and they were all overwhelmingly positive about her. When I was interviewing with her, she was transparent that, as a cardiologist, she was not sure she was the best person to get me, an exercise physiologist, where I wanted to go. I replied that I wasn’t sure where I wanted to go yet, but that I wanted to understand heart function. She agreed to do whatever she could to support me. Over the next 5 years, we established a fruitful collaboration and a plan for my next steps.

“Think carefully about what interests you, what is interesting to other people, and find a good person who will care about your success to help you get where you want to go.”

Beyond the Lab

What do you do outside of research?

In the summer, I spend a lot of my free time mountain biking. In the winter, I snowboard in Whistler. I started snowboarding on a tiny little hill in Ontario. That was actually part of the original draw to move out to BC. Well, to be honest, I have less time for these hobbies now, but it’s easier to get out and a lot more fun when I do. And I’ve had the chance to start doing more backcountry split boarding and touring and things like that. BC opened up possibilities that I couldn’t do well or easily in Ontario, so that’s been fun.

On November 12, 2025, HLI PIs Drs. Pat Camp and Graeme Koelwyn and Science and Grant Writers Drs. Kasia Adolphs and Evan Phillips participated in a Providence Research Trainee Collaborative Grant Writing Workshop.

During the session, moderated by PR Research Director Dr. Scott Tebbutt, panelists shared key strategies for writing fellowship and grant applications. Topics included the use of storytelling in grant writing, how best to align an application with funder priorities, balancing authenticity and strategic positioning, common pitfalls to avoid, handling rejection and re-submission, mentoring and leadership – and more.

Key Takeaways

✅ Tailor every application to the funder’s priorities and evaluation criteria.

✅ Use storytelling strategically to connect past experiences with future goals.

✅ Plan timelines early – avoid last-minute submissions.

✅ Engage authentically with EDI principles and community relationships.

✅ Seek feedback and mentorship to strengthen your application.

This event was part of a series of events organized by the Providence Research Trainee Collaborative to support trainees in successfully navigating their career paths. Following the panel discussion, trainees were encouraged to join a networking session, which provided the opportunity to explore and discuss topics further.

A big thank you to Kaylie Friess (Project Manager) and Josephine Jung (Director, Special Projects and Strategy) from Providence Research for organizing the event!

Story by Basak Ashley Sahin. Edited by Tiffany Chang.

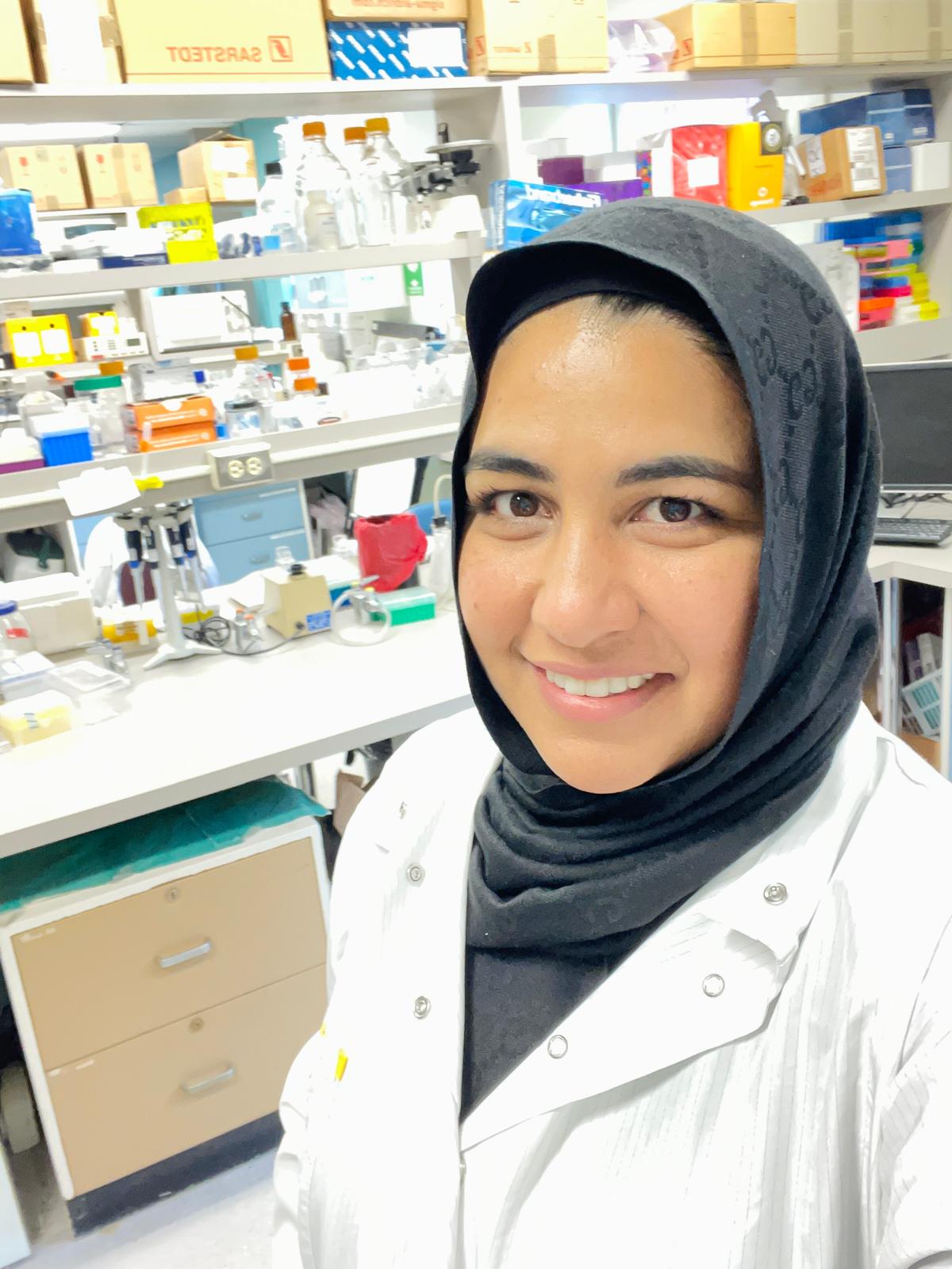

When Asma Tanveer moved to Canada from Pakistan 10 years ago, she brought with her a master’s degree in biotechnology and a passion for scientific research and its impact. Like many newcomers, she faced significant challenges in navigating credential recognition, an unfamiliar academic system, and the absence of accessible professional networks.

Asma is one of many trainees at HLI with a unique background and perspective. In June 2025, she was named HLI’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI) Person of the Quarter in recognition of her leadership, mentorship, and efforts to foster a more inclusive environment.

At HLI, Asma works on airway epithelial repair and drug responses in asthma models as a master’s student in the Dorscheid Lab in UBC’s Experimental Medicine program. She also contributes to outreach and mentorship through initiatives such as Geneskool: a Genome BC program that introduces high school students to genomics and biomedical research.

From personal experience to advocacy

Asma’s commitment to EDI is shaped by lived experience. “My commitment to EDI began with the realization that too many talented individuals are overlooked – not for lack of ability, but because of who they are. Having felt that invisibility myself, I was driven to act,” she says.

Since then, she has mentored women in science, contributed to outreach through Geneskool, and advocated for inclusion grounded in empathy and shared experience. “For me, EDI isn’t optional. It’s a responsibility to ensure everyone feels they belong.”

Her journey into biomedical research was shaped by mentors who offered support at key moments. She first connected with Dr. Sima Allahverdian, a former HLI researcher, through a mutual friend. Though Dr. Allahverdian had already relocated to Toronto, she generously offered guidance – recommending courses and encouraging Asma to pursue volunteer experience.

That connection led to an introduction to Dr. Gurpreet Singhera, a research associate at HLI and a manager of the Bruce McManus Cardiovascular Biobank. “Even with her full schedule, Dr. Singhera always made time for answering my emails or meeting for a coffee chat,” she says. “She helped me strengthen my application, introduced me to Dr. Del Dorscheid, and believed in my potential to contribute meaningfully to the lab.”

With their support, she joined the Dorscheid Lab as a graduate student. Looking back, she credits both mentors not only for their guidance but for modelling what inclusive mentorship looks like in practice. “Their belief in me made a lasting impact. It’s part of why I now feel so strongly about creating that same sense of welcome for others.”

Leading by example

Asma’s advocacy now includes mentoring early-career researchers, promoting inclusive lab practices, and contributing to outreach that reflects the diversity of communities served by HLI.

“EDI has shaped not just how I work, but why I work,” she says.“It’s helped me find mentors who value potential over credentials and communities that see difference as a strength. “

She believes inclusion begins with how people are welcomed and supported. “Sometimes, what holds people back isn’t a lack of talent, but a lack of confidence or the right platform to express themselves,” she says. “When we support others with respect and openness, we create the kind of environment where people feel seen – and when they feel seen, they shine. When they shine, we all benefit.”

That perspective was reinforced during a Mentor Walk session hosted by Tech2Step, where she was invited to speak on a science outreach panel. As the only racialized woman present – visibly Muslim, hijab-wearing, and of Pakistani and South Asian background – Asma says the moment reminded her that she was representing more than just herself.

“After the session, several attendees, especially young women, told me how much it meant to see someone who looked like them in that space. I realized I was part of something larger, a reflection of what’s possible.”

Creating space for others to thrive

Asma encourages others to take action, regardless of role or title.

“Start where you are. Improving EDI doesn’t require a title – small, consistent actions can create meaningful change. Your intention matters. The way you speak, listen, and show up shapes how others feel.”

She shares that there are many ways to contribute. She regularly offers coffee chats, connects friends and peers with professional opportunities, and volunteers as a parent at her children’s Catholic school and church events. She also leads an Islamic teaching circle in Vancouver – a space for reflection, learning and community building.

“In all spaces, I try to be of service in ways that honour others’ values and experiences – just as I hope mine are respected,” she says. “And I encourage others to do the same.”

Outside of the lab

Outside of her research and outreach work, Asma enjoys spending time with her husband and two daughters. They often play badminton together or unwind over a meal at The Old Spaghetti Factory, a family favourite in Vancouver.

“My family is my greatest source of strength and motivation,” she says.

Through her work, mentorship and advocacy, Asma Tanveer continues to advance both scientific inquiry and a culture of belonging, demonstrating that research and equity go hand in hand.

Job Description:

A Research Associate (RA) position is available at the University of British Columbia (UBC), Division of Respiratory Medicine, Department of Medicine under the direction of Dr. Scott J. Tebbutt, Professor of Medicine of UBC Faculty of Medicine and Principal Investigator and Director of Education of Centre for Heart Lung Innovation at St Paul’s Hospital.

The RA will work with an interdisciplinary and international team to support the Immunophenotyping of a COVID-19 pneumonia Cohort (IMPACC) Study. The RA and Dr. Tebbutt’s team members will identify molecular endotypes of long-COVID-19 (also called Post COVID-19 Syndrome) during and after COVID-19 infection, in peripheral blood, plasma, nasal swabs, and airway tissue samples, by carrying out unsupervised analysis of multi-omics profiles at a single time-point or considering the time-course profile during infection. Dr. Tebbutt’s team aims to characterize the molecular heterogeneity during COVID-19 infection and to develop biomarkers of prognostic significance as they relate to the development of long-COVID-19. The distinct molecular patterns associated with each endotype may, in turn, help elucidate novel mechanisms of action and inform drug discovery and repurposing efforts.

The RA will play a critical role in the project team, providing scientific and pulmonology-based expertise to support hypothesis generation, planning, coordination, and identification of host molecular endotypes associated with diverse COVID-19 outcomes and new variants in a longitudinal multi-omics cohort study of 1000 patients. The RA will be responsible for several domains, including, but not limited to: project coordination, critical evaluation of clinical data, applications for funding, communication with collaborators and stakeholders, The RA will provide additional support to the Principal Investigator and collaborators as needed. The COVID-19 pandemic has created a climate of rapidly evolving information, goals and questions, and the RA will be expected to respond quickly and adapt to changing demands and short timelines.

Responsibilities will include, but will not be limited to:

- Performing critical evaluation of clinical data

- Analysis of experimental data, statistical analyses (including omics), preparation of manuscripts and scientific reports, and dissemination of research findings.

- Being current on emerging COVID-19 interventions and models of care, including in the respiratory space

- Performing literature and systematic reviews relevant to above-noted goals

- Facilitating the development of scope and strategies for research registries

- Developing reports and manuscripts for publication

- Preparing and delivering presentations for research meetings

- Coordinating and developing grant applications

- Preparing background documents for stakeholder meetings

- Participating in stakeholder engagement meetings

- Coordinating research activities and chairing and co-chairing research team meetings

- Providing other support as required to Dr. Tebbutt, researchers and team

Requirements:

- MD and MSc degree with 3+ years of relevant postdoctoral experience in respiratory medicine or thoracic research

- A minimum of 5 years of clinical work experience in respiratory/thoracic medicine

- Extensive experience and knowledge of metabolomics, acute lung injury, and preclinical drug development

- Extensive research experience of COVID-19 studies

- Demonstrated high-quality publication record in COVID-19 research: i.e., multiple first-author publications about COVID-19 in high-impact journals such as NEJM, Lancet, Lancet Respir Med, JAMA, JAMA Intern Med, BMJ, AJRCCM, PNAS, etc.

- Experience in studying biomarkers for diagnosing complex diseases of the lungs

- Demonstrated a successful track record of grant (e.g., CIHR) applications (as a co-applicant or applicant)

- Demonstrated experience in managing multiple projects with conflicting timelines and priorities, and excellent time-management skills

Duration and salary:

The position will begin March 1, 2026 for a period of 1 year with the possibility of extension.

Salary is $76,128.00 per annum plus benefits.

Application:

The deadline for interested individuals is December 10, 2025. Applicants should send a cover letter and curriculum vitae to Dr. Tebbutt: scott.tebbutt@hli.ubc.ca

Equity and diversity are essential to academic excellence. An open and diverse community fosters the inclusion of voices that have been underrepresented or discouraged. We encourage applications from members of groups that have been marginalized on any grounds enumerated under the B.C. Human Rights Code, including sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, racialization, disability, political belief, religion, marital or family status, age, and/or status as a First Nation, Metis, Inuit, or Indigenous person.

All qualified candidates are encouraged to apply; however, Canadians and permanent residents will be given priority.

If someone had told me back in my university days in India that I would one day be working with human hearts and lungs, I would have laughed in disbelief. Back then, the world of cardiopulmonary research seemed galaxies away from the microbiology degree I was pursuing.

Life, however, has a way of surprising us. In the summer of 1996, I immigrated to Canada, armed with a PhD in Microbiology, a daunting leap into a new country and a new future. In January 1997, I began my research career at the University of British Columbia in the Department of Microbiology. Those early years were a mix of learning and transition, marked by both professional growth and personal milestones, including a period of maternity leave that reshaped my perspective on work-life balance and resilience.

In August 2000, I joined what was then the McDonald Research Laboratories, today known as the Centre for Heart Lung Innovation (HLI). Walking into the Centre for the first time, I remember feeling both nervous and hopeful. What I didn’t know then was that this place would become my second home in Canada, a space where my professional identity would take root and flourish.

My journey at HLI began in pulmonary research under the mentorship of Dr. Del Dorscheid, who placed his trust in me as a Research Associate and his lab manager. I took on both independent projects and collaborative research initiatives. His faith in me taught an enduring lesson: growth often begins when someone believes in you before you fully believe in yourself.

In academia, research careers depend on funding cycles, shifting priorities, and constant change. With that understanding, I sought to broaden my expertise and prepare for new directions. I had always been fascinated by the work being done in the Cardiovascular Tissue Registry (CVTR) at HLI now known as the Bruce McManus Cardiovascular Biobank (BMCB). When the opportunity arose, I became a member of the explanted heart retrieval team. Today, as the manager of the BMCB, I am not only part of the exciting advancements in the cardiovascular field, but I also witness the human side of science every day. When heart transplant recipients visit the biobank to see the heart that once sustained them, their stories of gratitude and resilience remind me that research isn’t only about experiments or data, it is about people and their wellness.

Beyond research, I have always believed in the importance of mentorship and giving back. Since 2008, I have helped organize HLI’s High School Student Week Mentorship Program, which introduces Grade 11 and 12 students into biomedical research. Over the years, I have had the privilege of mentoring more than 250 students. Watching them discover their passion and pursue their careers has been one of the most rewarding parts of my journey.

Soon, HLI will transition from its historic downtown Vancouver location to the Clinical Support and Research Centre (CSRC) at the new St. Paul’s Hospital. It will be a shift from a historic location to one that is futuristic, and I am excited and grateful to be part of this transition. Still, the walls of our current home hold memories that will always stay with me.

In August 2025, I celebrated twenty-five years at HLI, a milestone that fills me with immense gratitude. Looking back over these two and a half decades, I am thankful for the mentors who guided me, and for the colleagues who became lifelong friends. Leaving my family and friends in India was one of the hardest choices I ever made, but the community I found at HLI filled that space with belonging and purpose.

HLI has taught me far more than science. It has helped foster my development as a leader, strengthened my resilience, and deepened my gratitude. It has shown me that growth does not happen in isolation, it happens in communities that believe in one another. For me, that community has always been HLI, and for that, I am deeply thankful.