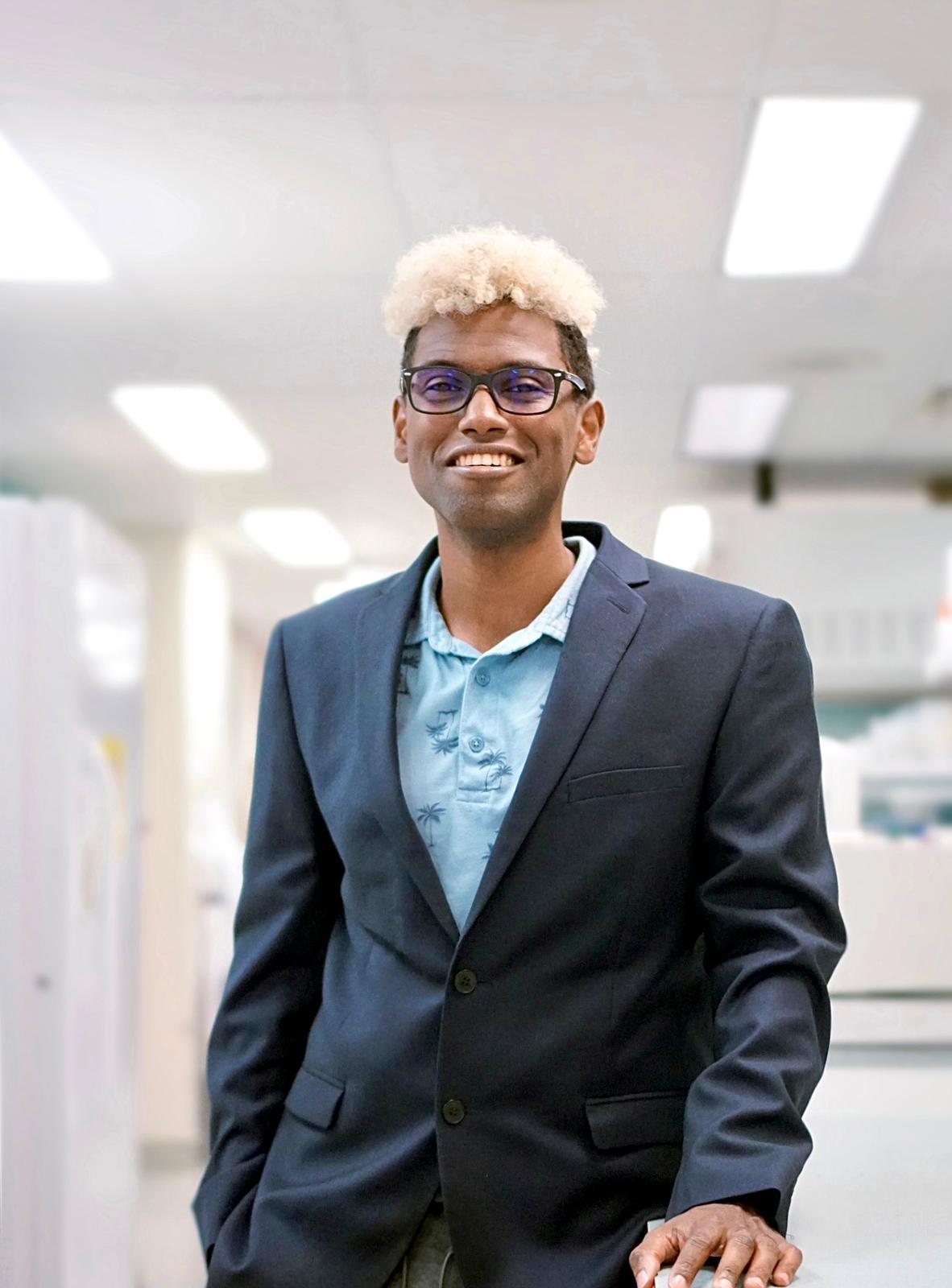

Dr. Yasir Mohamud is a postdoctoral fellow at HLI, the UBC Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, and a recipient of the inaugural CIHR Research Excellence, Diversity, and Independence Early Career Transition Award. During his doctoral training in the laboratory of Dr. Honglin Luo, his research identified ways in which enteroviruses contribute to viral heart inflammation, or myocarditis.

What is your educational background?

My educational background is quite unique. I didn’t go to school until I was nine, which was when I came to Canada, when I entered Grade 4. In my home country Somalia, depending on the region you grew up in, you were lucky if you got home schooling. So once I finally started school, I fell in love with it. That experience of being hungry for knowledge, having been deprived of it in the early stages of my life, really inspired me to pursue learning. It was also something my parents always encouraged, so that motivated me more, and I became the first person in my family to complete a bachelor’s degree. I then did my master’s in Biochemistry at the University of Ottawa before coming to BC for my PhD.

How did you grapple with a new country and a new education system?

It was a bit of a shock, but in a good way. I was overwhelmed by the new knowledge and new experiences, but I also absorbed it all like a sponge. I have a big family; my parents had 10 kids, but with two brothers close to my age, having them around and experiencing everything with them for the first time was really enjoyable. Even something like discovering that there was such a thing as a TV. Watching television was an entirely new experience. I remember watching television and doing my homework at the same time, it was so interesting.

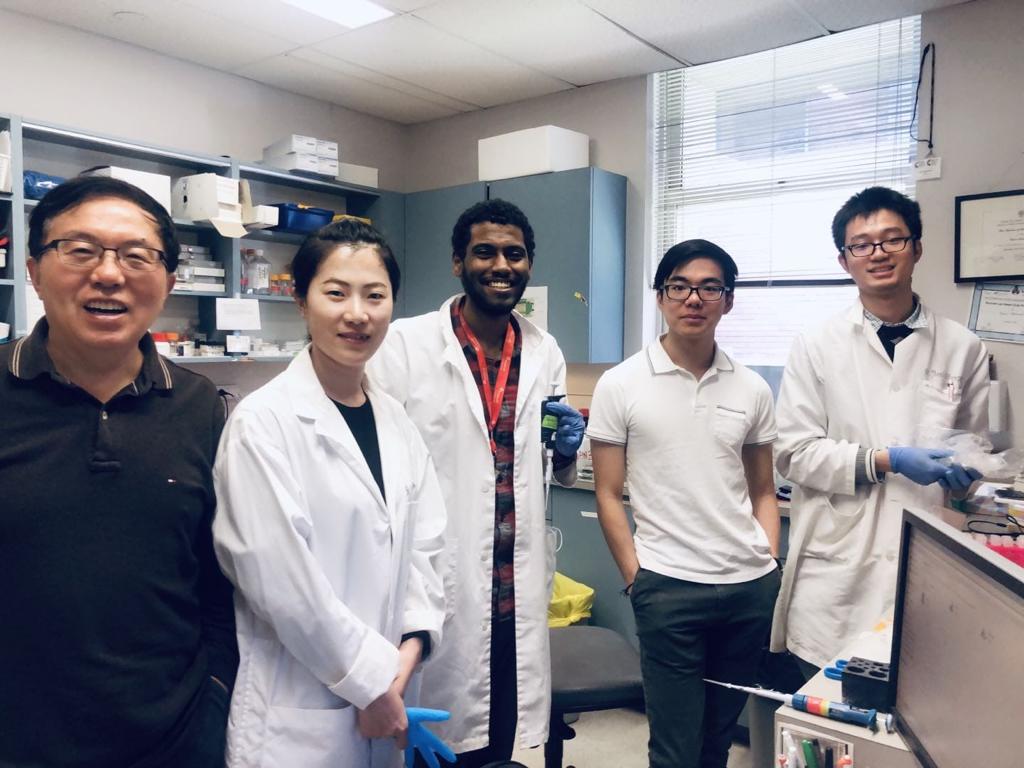

What are you currently researching at HLI?

Right now, I’m a postdoctoral fellow in Dr. Honglin Luo’s lab, and I’ve been in this role for almost four years. Our lab studies how viruses can target the heart, harm the heart, and lead to heart failure. Viral heart failure is rare, unpredictable, and can have devastating outcomes—even though we all get infected by viruses routinely throughout the year. In fact, some individuals can lose their entire heart and require a heart transplant. This really motivates us to study viral heart infection to see what we can do to improve things for patients.

What is one of your proudest moments from your career so far?

That’s a really good question because it’s something that I don’t often think about. I feel like I’m very forward-driven and always thinking about the future. Maybe it’s a naïve mindset, but I think this drive inspires me to pursue new opportunities and never to settle. I know my family is very proud of me for being the first person to graduate from university and obtain my PhD. These are great milestones, but I’m not thinking about them at this stage in my life. Maybe a few years down the road, I’ll be able to look back and say “These were proud moments for me.” After all, it is something that shouldn’t be taken for granted; there are a lot of places in the world, like where I came from, where it’s very rare to have someone complete a bachelor’s education.

You’ve had a lot of volunteer experience, especially with the clinical side of things, interacting with patients of all ages. How have those experiences shaped you as a person?

This question really takes me back. Yes, I was volunteering at the Perley and Rideau Veterans’ Health Centre in Ottawa, at least a decade ago now. I was quite young, in the early stages of my undergrad, but I was trying to get volunteering experience in a setting where I would be able to interact with patients. This was important to me because I always considered medicine—becoming a doctor—as a potential career path. I think interacting with those patients let me see a different side of medicine. I learned a lot of rich stories from talking to the people there. Many of them had Alzheimer’s disease, but these people had been through so much. A lot of them were veterans, so they had experience of being in war, and memories of how life used to be 50, 60 years ago, things you only read in books. It’s really interesting to hear these things from a person that lived them, and it was here I learned the importance of listening as a skill. It has definitely served me well in my academic journey.

Your goal is to stay in academia and become a principal investigator (PI). But it seems like you’re in the minority of trainees for wanting to do so. Why do you think that is? What barriers are there to becoming an academic?

That’s another really good question. I think a lot of our trainees are undergraduate students or master’s students, so it’s possible it is just a bit early for them to be thinking about their long-term career paths. But I think it’s an excellent career choice because being a PI combines a lot of the things that we go into academia for, which is our love of knowledge, research, and a passion for science. It is a career that gives you a lot of independence, but also the ability to work within a team and get diverse perspectives to work towards a common goal. I think it is really an admirable career to be a researcher or a PI, and I think a lot of people would like to do it, but it is difficult to succeed because there are so few positions available. I heard a statistic that only around 5-10% of trainees that progress through the academic trajectory end up making it to the PI position. Maybe people feel like it’s a little unattainable?

What are your experiences with teaching?

To be honest, I love teaching and really enjoy interacting with students. I have lectured graduate level courses at HLI including PATH 521 and MEDI 570, and I like to see how my students learn by asking them questions and seeing how they respond. That dynamic interaction is something I wish that I had more of when I was going through my education. I think students learn by making mistakes; I always tell them “It’s okay if you get the answers wrong”, and I try to make it fun for them, like a game, where they get to answer questions and they get points and there’s a reward.

Are there any changes or improvements that you would like to implement in academia as you move up the ladder?

Once I become a PI, one of my goals would be to listen to trainees more. Trainees have a lot of suggestions on how to improve their programs and research environment, but they don’t really have an ear to listen to that input. Maybe they don’t have someone they feel comfortable enough to go to and say “I think this could be changed and improved.” Also, I want to know what we can do for the trainees. Maybe they have trouble with work-life balance or their research isn’t progressing as well as they would like. That’s where we can step in and ask them how we can help. Ultimately, we all want to succeed, but we need to be able to help one another to reach that goal.

You had the unique opportunity to study COVID-19 when it was only known as the novel coronavirus. How does that compare to the virology work that you usually do in Dr. Luo’s lab?

At the end of the day, scientists love to learn. My work in the Luo lab involved studying coxsackieviruses, which are cardiotropic RNA viruses, and their role in heart infection, inflammation and failure. But when COVID-19 hit, I was able to translate my coxsackievirus knowledge to studies involving SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID. I think that’s what I really enjoyed about my graduate experience, learning the skills to equip me to look at whatever new virus emerges—so that even if there’s a Virus X that comes from a different planet, I will be ready.

What is your favourite quote?

It’s a quote I always tell our students and trainees: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, expecting different results.” I love it; it resonates with me a lot as a researcher because it emphasizes the importance of innovation and trying new ideas to solve challenging problems. I like to tell our trainees, every failed experiment is an opportunity to learn, improve, and come back stronger!

Researchers are often focused on their niches, like coxsackieviruses, which many people might not have heard of. How do you explain the significance of your experiments and work—studying things over and over again—to the average person?

Actually, during my graduate studies, I hadn’t heard of coxsackieviruses either, since it is quite a rare virus. For me, the answer to that question is that in science, we use specific tools and models to study larger problems. To us, a coxsackievirus is a tool, a model virus we use to study how infectious disease affects the heart, which is a big problem. As researchers, we can see these links and how our work connects to different, broader, more important disease outcomes. A lay person may just see the virus and ask “This no-name virus, why are we even studying it?” But we are asking important questions like “How does this virus cause this disease?” and “How does viral infection affect patients with COPD and other common diseases?” Of course, answering these questions takes time, and in science, we’re often in the early, early stages of the process.